- Sale

- What's New

- Trending

-

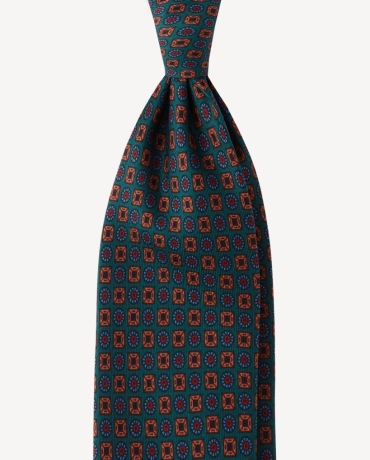

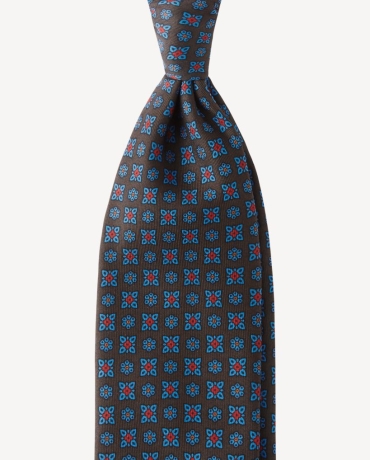

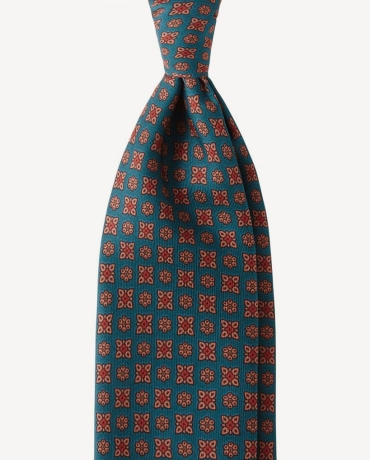

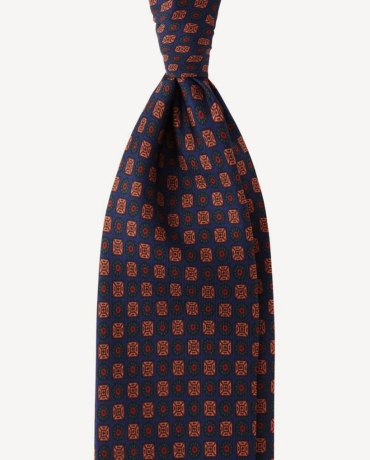

Ties

![]()

![]() CategoriesConstruction

CategoriesConstruction - Bespoke Ties

- Eyewear

- Jewellery

- Shirts

-

Clothing

Collections

- Shoes

- Accessories

- Home & Lifestyle